Is depression a fate?

For years, mental health experts have claimed that depression is a byproduct of a chemical imbalance in the brain,

However, in recent years, science and medicine have come up with new understandings, due to the ineffectiveness of the current treatment for depression.

We are beginning to understand that depression is not related to a chemical imbalance in the brain as was previously thought.

I, for example, who has studied people, and not just studies, am sure that it is possible to overcome depression through fundamental and consistent changes in life such as meditation, exposure to sunlight, exercise, dietary changes, and taking responsibility for one’s life.

But this approach can be used by “experts” who are accustomed to the idea that humans tend to fall ill and depressed for no apparent reason and that they or science are the only salvation.

But it’s not just the experts, our culture has become accustomed to prioritizing the normalization of victims.

And I’m not talking about those who suffer from depression, I’m talking about the narrative in our culture.

I personally do not see people as victims, since every Ivy League member believes in this approach, it creates a big gap between me and them.

But I am not willing to let people who do not believe in the strengths that exist in each and every one of us and in the opportunities inherent in the challenges that come to us lead the narrative anymore.

As long as we normalize illness, whether it is physical or emotional, and when I say normalize, I mean the perception that these situations are a decree of fate that fell on us from heaven for no reason, and as long as we do not choose to learn from these situations and how we can turn every challenge into an event designed to improve our lives – we remain victims.

Don’t get me wrong, if we did not know that it is possible to overcome depression – I would not be writing this.

But as long as there is one person who did succeed, the only narrative that should be in the norm is how to get out of it and not how to normalize that it is impossible to get out of it.

Many people have managed to cure themselves of deep depression, certain stories have become habits of millions around the world, such as the story of Wim Hof’s healing, who overcame depression after his wife committed suicide.

Only the focus is on ice baths and not on how he used them to recover – but how many people do you know who would be willing to enter a frozen lake every day for months to change their lives?

None of this means that I don’t believe that depression is a complex condition. We’ll get to that later.

I recently read an article by psychologist Dr. Yaakov Ophir entitled “The Hypothesis in the Eye of the Storm: The [Failed] Biomedical Revolution in Psychiatry Underlies the Mental Health Crisis.”

I use various quotes from him in the rest of the text, and I invite you to read it as well.

Yaakov talks about how, despite scientific progress, the rates of distress and the demand for treatment are only increasing.

And the hypothesis is that the dominant concept in psychiatry may have actually worsened the public’s sense of mental well-being.

For this to be the case, experts need to be more aligned with the belief that depression is a fate that comes without a reason, and therefore that the victim should be justified or saved rather than given strength and support so that he can overcome his challenges.

According to the World Health Organization, about 280 million people worldwide suffer from depression.

In the US, about half of young adults (18-44) reported in 2023, in a survey by the American Psychological Association, that they suffer from some kind of mental disorder (APA, 2023).

In Sweden, a huge study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA Psychiatry) found that approximately 80% of the population has received a diagnosis or prescription for psychiatric medication during their lifetime (Kessing et al., 2023).

So despite scientific advances, the rates of distress, diagnoses, and demand for treatment are only increasing significantly in the fields of psychiatry, psychology, and social work.

In moments of pain, the need to take medication is very understandable to me, I too will take a painkiller in times of suffering in order to function.

And there is no shortage of situations in which medications save lives and help people overcome challenges, however, we all know that medications do not cure, have long-term side effects, and in many cases they cause us Ignore the root of the problem.

Medical arrogance

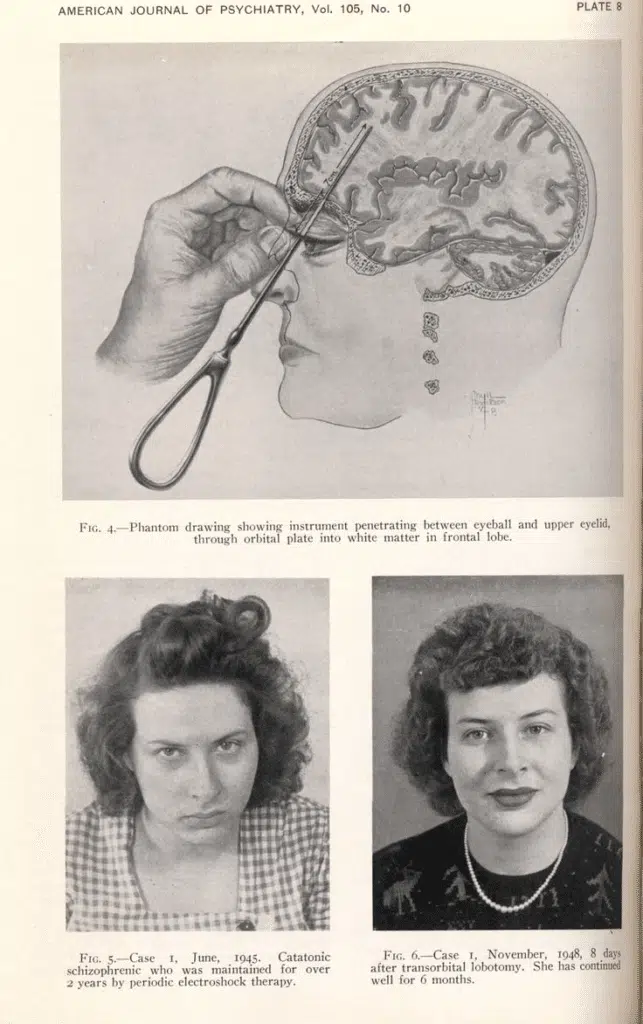

Despite historical approaches and events, such as various cruel treatments that left the patient much worse off than they were, which have been proven to do more harm than good, there is a certain arrogant attitude in the world of medicine, brain research, psychology, and psychiatry that only what science and research have revealed is the truth.

But has this always been the case?

Let’s go back in time.

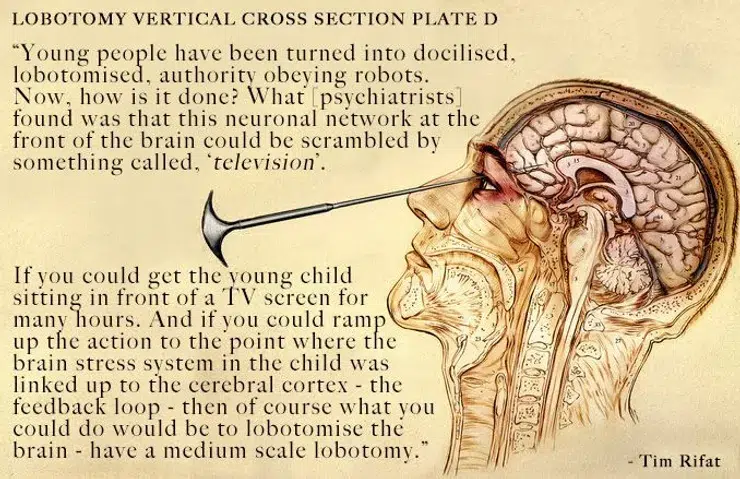

Before the era of psychiatric drugs, one way to treat depression was through surgery.

Thousands of patients underwent surgeries to sever connections and remove parts of the prefrontal cortex.

This surgical intervention was considered the cutting edge of science in the 1940s.

It was seen as an effective and precise strategy for relieving mental pain (Freeman & Watts, 1942) and even earned its inventor, Portuguese neurologist Egas Moniz, a Nobel Prize. Despite the scientific consensus of the time, over the years it became clear that lobotomy was a cruel experimental intervention that caused serious and irreversible damage (Terrier et al., 2019).

It is not for nothing that lobotomy has been condemned from wall to wall and has become a symbol of the dangers of medical hubris in psychiatry. But it is not the only intervention that has been taken off the shelves in disgrace.

The history of medicine is replete with stories of ‘safe’ drugs that were discovered over the years to be deadly substances, such as opioids, the addictive painkillers that are especially common in Israel (Davidowitz et al., 2023), and we know of hundreds of drugs that were banned for use only after they were distributed to the public, even though they had all the necessary safety approvals (Onakpoya et al., 2016).

“Psychiatric drugs are drugs.”

Amphetamines, for example, which are intended to ‘treat’ attention deficit disorder, are called ‘speed’ in street slang. Psychiatric drugs are mind-altering substances, and are prohibited by the Dangerous Drugs Ordinance without a medical prescription.

Psychiatric drugs are not cures.

They may relieve pain or increase function (temporarily), they may be given in careful doses and under medical supervision; but many of them are not fundamentally different, chemically and in terms of how they act on the human brain, from other mind-altering drugs.

Like other drugs, psychiatric drugs also penetrate the blood-brain barrier (which is designed to protect the brain from harmful toxins) and interfere with the process of synaptic transmission.

And like other drugs, when used over time, psychiatric medications are likely to trigger the brain’s compensatory mechanism (called pharmacodynamic tolerance) that reduces their effectiveness in the long term and increases the risk of developing dependence and addiction (Poulos & Cappell, 1991).

In the world of psychiatric medications, there is a battle over the narrative about how they work, but in practice, it is difficult to deny that psychiatric medications create an artificial disruption in biochemical processes that occur naturally in the brain.

Some psychiatric medications, for example, inhibit the reuptake of certain neurotransmitters. There may be some temporary gains in this, but at the end of the day, it is a disruption of the synaptic transmission process and a direct effect on the biochemistry of the brain.

Forty-five years ago, the percentage of children who took stimulant medications on a daily basis was zero.

Today, there is hardly a home without a prescription.

We chose to restrain energetic and frenetic (mostly healthy) children (mainly boys) using chemical substances.

We ‘treated’ problems in the field of education using chemical substances that we know create dependence (physiologically and/or psychologically), that we know depress the body and mind, and that we know that there is no fundamental difference between them and other stimulant drugs (Ophir, 2022b).

In other words, the same medication for attention and concentration that is given to more young people can be the cause of deterioration in emotional states later on.

So is depression a consequence that indicates the deterioration of the genetics of the human race?

Or is it worth and desirable to assume that something in the advanced lifestyle, technology, lack of a sense of meaning, and a minimum of learning about mental control and mental balance are also relevant?

I’ve thought a lot about this topic since the “Internet Storm.” Of course, I also called Dr. Yaakov Raz and Dr. Nader Bhutto to go deeper beyond my own insights.